The Grand Canal: carrying the Chinese culture for thousands of years

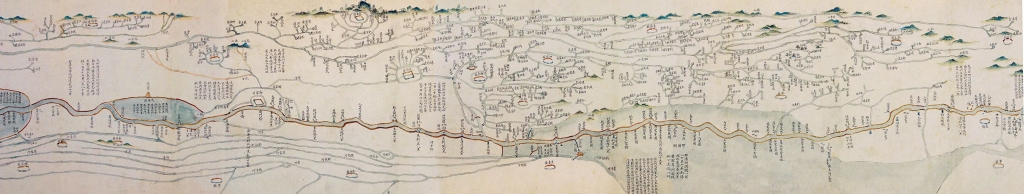

The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal starts from Yuhang (now Hangzhou) in the south and ends at Zhuojun (now Beijing) in the north. It is the longest canal in the world. It can be called a "living corridor of cultural heritage". Historically, the Grand Canal was the main artery connecting the north and south of China. Emperors inspected provinces by boats and commoners depended on the Canal for their livelihoods. Densely populated with scenic spots, the Great Canal made an enormous impact on the economic and cultural development and exchanges between the north and south of China. On 28 April 2022, the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was navigable once again in a century. Having carried the Chinese culture for thousands of years, this ancient canal starts a new chapter of its history.

Author: Prof. Sui-Wai Cheung, Chair and Professor, Department of History, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

According to a Chinese proverb that was once popular, “the Yellow River is a prodigal son, the Grand Canal is an inexhaustible box of jewels to support the family". The Yellow River is a natural river. For thousands of years, it was the birthplace of Chinese civilization but also responsible for countless floods. The Grand Canal was a man-made river in the Ming and Qing dynasties. It supported the “golden age” of late imperial China.

The Sui as the first dynasty to build canals on a large scale

The administration of the large empire of China was not easy in a period without modern technology. The emperor understood that so long as the capital was stable, the empire would have a centre from which he could send reliable soldiers to handle local rebellions at any time. As such, the emperors of the Sui dynasty (581-619) stationed over 100,000 soldiers permanently in the capital, Daxing (Xi’an). However, this created a question of how these soldiers stationed at the capital and its surrounding areas (in addition to officials and imperial families) could be fed. Daxing was in Shaanxi where food production was low and would not be sufficient to feed the soldiers.

The Sui Dynasty government decided on a solution. They would use manual labour to create a river to connect the capital, Daxing, to the agriculturally fertile Jiangnan (regions south of the Yangtze River). They could then extract a steady stream of grain tax from Jiangnan to the capital. This was also what historians called “using Southeastern wealth to feed the Northwestern troops”. This grain shipped from the local areas to the capital became known as grain tribute.

However, constructing the canal was an enormous project. Apart from digging the course of the river, the government still had to build a separate channel to allow natural river water flow into the canal. Due to the huge scale of the project, the Sui Dynasty government could only build the canal in stages. Beginning the project from the beginning of the reign of the first Sui emperor (Emperor Wen of Sui, r. 581-604), it was only finished during the reign of the second Sui emperor (Emperor Yang of Sui, r. 604-618). This canal from Yuhang (Hangzhou) to Daxing ran through the Yangtze River and Huai River and arrived at Luoyang and Daxing on the Yellow River’s southern banks. Once the canal was built, Emperor Yang was extremely pleased. He reportedly declared that he had already toured the route from Daxing to Jiangdu (Yangzhou) on a dragon boat three times. Emperor Yang also used the canal to carry soldiers and supplies to support his wars. In 608, to support a military expedition to the Goryeo dynasty, he built another canal. This was the Yongji canal which passed through the Yellow River and flowed northwards to reach the North China Plain.

The Sui dynasty was the first in China to build a large-scale canal. Even though the Emperor Yang of Sui was always criticized by his contemporaries for causing the collapse of the Sui dynasty by wasting resources and labour, he had effectively demonstrated to later emperors on how canals could be used to support the unification of China.

Sea transportation of grain tribute in the Yuan dynasty

In 1279, Mongols wiped out the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279). Under the rule of Kublai Khan, the founding emperor of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), Beijing became the capital of a unified China for the first time. Though the Mongols were nomadic tribes, like the Sui dynasty, Khan too had to resolve the same problem of how to feed his garrisoned troops at his capital.

Building a canal necessitated an enormous amount of manpower and resources. As an alternative, Kublai Khan decided to use coastal routes instead to bring rice from Jiangnan to Beijing. This was a brave pioneering attempt for the time. Though fishing along the Chinese coast began in the prehistoric era, the long coastal journey between the north and south was untraveled and unique. In 1282, the Yuan dynasty government recruited two active and experienced pirate captains in the Jiangsu and Zhejiang coastal regions, Zhu Qing and Zhang Xuan, to try shipping grain along the coastal route. The Yuan dynasty hoped to rely on their strong sailing experience to find the fastest grain transport route to the north. In the eighth lunar month that year, Zhu Qing and Zhang Xuan began their first trial voyage using sixty flat bottomed sand boats carrying a total of 46,000 piculs of white rice. They started from Liujia port in the Yangtze River delta and sailed northwards along the coast. But this first voyage from the south to the north was not smooth. When the crew arrived at the Shandong peninsula, it was winter and the surface of the sea began to freeze. The fleet could not continue until spring arrived and the ice thawed. In 1283, the fleet finally arrived at Tianjin’s coast. But, they discovered that the rivers in Tianjin were too shallow for their ships. The fleet would need to unload the grain at Tianjin and return south. This whole Northern expedition took around seven months. However, this pioneer journey allowed the sailors of the Yangtze delta to understand Northern Chinese coastal winds, and terrain. From then on, the coastal route became the main grain shipping route for the Yuan dynasty. By the end of the Yuan dynasty, over 3,000,000 piculs of grain were shipped each year from the Yangtze delta to the capital of Beijing using the coastal route.

Constructing a waterway between southern and northern China in the Ming

In 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang who founded the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) established the capital in Yingtian prefecture (Nanjing). Though he went to a lot of trouble to build the city of Nanjing, he avoided the trouble of building a canal. Nanjing is located in the lower valley of the Yangtze river and was therefore a location combining the political and agricultural centres into one.

The beginning of the Grand Canal in late imperial China originated from the death of the founding Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang. Zhu Yuanzhang died in 1398, his grandson Zhu Yunwen succeeded to the throne as the second Ming emperor, the Jianwen Emperor. He was immediately confronted by political problems, namely the threat of his uncles in charge of guarding the north. To consolidate his regime, the Jianwen Emperor ordered a removal of their positions, which led Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan based in Beiping (now Beijing), to rebel. Zhu Di declared that the Jianwen Emperor had been affected by evil counsellors, and rebelled. In 1402, Zhu Di conquered the capital of Nanjing. The reign of the Jianwen Emperor was over.

In 1402 Zhu Di became the new emperor of the Ming dynasty. He formally renamed Beiping as Beijing, literally meaning capital of the north, and repeatedly emphasized to his court councillors that the northern borders were unstable and needed him to safeguard. In 1406, he ordered the conscription of the labourers for renovating and enlarging the former capital of the Yuan dynasty. In 1409, the Yongle Emperor went on an imperial tour to the northern capital for the first time. In the same year, he returned to Nanjing. In 1413, the Yongle Emperor made his second northern tour. This time, he stayed in Beijing for three years and did not return to Nanjing until 1416. His intention to move the capital to Beijing was very clear. The Yongle Emperor did not move the capital for a long time because apart from rebuilding the palaces left by the Yuan dynasty, he also wanted to focus on building a Hangzhou to Beijing Grand Canal.

The Yongle Emperor, following Emperor Yang of the Sui, once again built a large-scale canal to improve transport between the capital and the rest of the China empire. He abandoned the Yuan Dynasty’s method of shipping grain by the coastal route. Japanese historian Hoshi Ayao suspected that this was to prevent the water transport from being attacked by pirates along the coast at the time. The reason for this was that from an administrative point of view, it was easier to supervise a canal than to supervise an ocean. However, the cost of building the canal and diverting water to fill it was far higher than the cost of shipping by sea.

The construction of the canal during the Yongle period can be divided into three parts. The first was building the middle section of the canal using the existing river channels, especially the Yellow River. In the second part, the Ministry of Works minister, Song Li, in Shandong conscripted 300,000 people to build a canal between Xuzhou (city beside the Yellow River) and Linqing in the north. It was named the Huitong Canal. The construction was completed in around 1412. In the third phase, at Huai’an, the Qingjiangpu Canal was built.

In 1415, the Yongle Emperor ordered Duke Chen Xuan to build 3,000 boats in Huguang (Hunan, Hubei), Jiangxi and other places, and bring a trial load of 3 million piculs of rice from the Yangtze delta to Beijing. However, Chen Xuan soon discovered when the ship reached Huai’an, they needed to travel by foot on a short road on land before they could reach the Yellow River. The ships were placed on rollers made of tree trunks and men and animals were used to move the ships along the road to the Yellow River. This method of transportation was obviously arduous, slow and costly. In response to this transportation problem, Chen Xuan ordered the construction of a short canal from Huai’an city to Qingkou, where it joined the Yellow River. This canal was called the Qingjiangpu Canal.

When the Huitong Canal and the Qingjiangpu Canal were completed, grain shipping fleets could finally sail from Hangzhou northwards to Tianjin. The Ming government built many granaries in Tianjin to receive rice from the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and arranged vehicles to continuously transport the grain to Beijing. In 1417, the emperor once again toured the north. This time, he simply stayed in Beijing and did not return to the south. In 1420, the construction of the Beijing Palace was completed and the Yongle Emperor ordered the crown prince to move from Nanjing to Beijing. On Chinese New Year’s Day in 1421, the Yongle Emperor officially announced that Beijing would be the new principal capital (and Nanjing became the secondary capital).

The Yongle Emperor established the main waterway between the north and south of China for the Ming and Qing dynasties. Compared with land transportation, the shipping route was cheaper and could facilitate economic and cultural exchange between Jiangnan and Northern China. Though the Grand Canal was constructed for a political reason, over 7,000 junk ships sailed through the Grand Canal every year from spring to fall. Merchants also took the opportunity to transport goods. This provided a gigantic stimulus to the market development of coastal cities.

Grand Canal and the emergence of golden age in the Qing

After Yongle’s period, the policy of future improvements to the Grand Canal was mainly to keep it away from the Yellow River. At that time, the main part of the canal which used the Yellow River was the 300 Chinese mile section between Qingkou (the northern end of Qingjiangpu) to Xuzhou (the starting point of Huitong Canal’s south side). The Yellow River flowed down from the west, and the current was very strong. Near Xuzhou, the riverbed had many sharp rocks, creating whirlpools. Junk ships at this section of the Yellow River had to sail against the current and often capsized. As such, during the Ming Dynasty to Qing Dynasty, the Chinese government had continuously to build canals, including New Nanyang Canal (1567), Jia Canal (1605), New Tongji Canal (1623) and the Zhong Canal (1686).

After almost three centuries of hard work, the 1,700-kilometre-long Grand Canal which spanned five provinces was finally completed. Apart from Qingkou, which was the junction between the Yellow River and the canal, the Grand Canal was completely free from the influence of the Yellow River. It sent millions of piculs of grain from the Yangtze provinces continuously to Beijing. This created a period of abundance and economic prosperity for the Yangtze delta and canal cities.

In 1855, the Yellow River burst and changed its course, which destroyed the dykes and dams of the Grand Canal and brought huge amounts of silt into it. The "inexhaustible box of jewels" was severely damaged. After the middle of the 19th century, while China faced serious internal and external pressures, the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, which used to be the “North-South Artery”, was damaged beyond repair and was abandoned. The Canal since then ceased to function and the Qing dynasty began to decline. In recent years, the Grand Canal has received attention and protection. On 28 April 2022, the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal was navigable again after having been abandoned for more than a century. Many sections which had been un-used for decades have regained their former vitality. The Grand Canal, once again, benefits the people living on both sides of the riverbanks.

扫描二维码分享到手机